You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

The body appears to fight to get back to a set point!

- Thread starter Gmat

- Start date

Help Support Bariatric & Weight Loss Surgery Forum:

http://www.nytimes.com/2016/05/02/health/biggest-loser-weight-loss.html - you may need a subscription to read it. And in copying, the formatting didn't always work.

After ‘The Biggest Loser,’ Their Bodies Fought to Regain Weight

Contestants lost hundreds of pounds during Season 8, but

gained them back. A study of their struggles helps explain

why so many people fail to keep off the weight they lose.

By GINA KOLATAMAY 2, 2016

Danny Cahill stood, slightly dazed, in a blizzard of confetti as the audience screamed and his family ran on stage. He had won Season 8 of NBC’s reality television show “The Biggest Loser,” shedding more weight than anyone ever had on the program — an astonishing 239 pounds in seven months.

When he got on the scale for all to see that evening, Dec. 8, 2009, he weighed just 191 pounds, down from 430. Dressed in a T-shirt and knee-length shorts, he was lean, athletic and as handsome as a model.

“I’ve got my life back,” he declared. “I mean, I feel like a million bucks.”

Mr. Cahill left the show’s stage in Hollywood and flew directly to New York to start a triumphal tour of the talk shows, chatting with Jay Leno, Regis Philbin and Joy Behar. As he heard from fans all over the world, his elation knew no bounds.

But in the years since, more than 100 pounds have crept back onto his 5-foot-11 frame despite his best efforts. In fact, most of that season’s 16 contestants have regained much if not all the weight they lost so arduously. Some are even heavier now.

Yet their experiences, while a bitter personal disappointment, have been a gift to science. A study of Season 8’s contestants has yielded surprising new discoveries about the physiology of obesity that help explain why so many people struggle unsuccessfully to keep off the weight they lose.

Kevin Hall, a scientist at a federal research center who admits to a weakness for reality TV, had the idea to follow the “Biggest Loser” contestants for six years after that victorious night. The project was the first to measure what happened to people over as long as six years after they had lost large amounts of weight with intensive dieting and exercise.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Photo

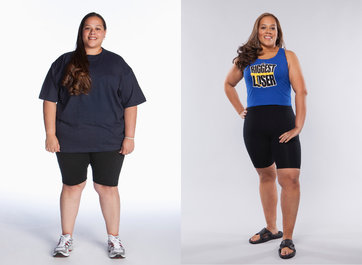

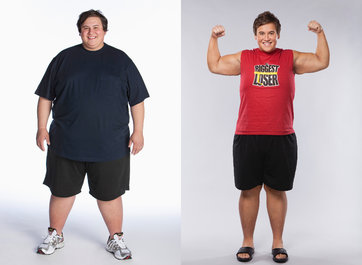

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal, via Getty

“I won’t be victim to this. It’s the hand I’ve been dealt.”

Danny Cahill

46, speaker, author, land surveyor and musician, Broken Arrow, Okla.

WEIGHT Before show, 430 pounds; at finale, 191 pounds; now, 295 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 800 fewer calories a day than would be expected for a man his size.

The results, the researchers said, were stunning. They showed just how hard the body fights back against weight loss.

“It is frightening and amazing,” said Dr. Hall, an expert on metabolism at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, which is part of the National Institutes of Health. “I am just blown away.”

It has to do with resting metabolism, which determines how many calories a person burns when at rest. When the show began, the contestants, though hugely overweight, had normal metabolisms for their size, meaning they were burning a normal number of calories for people of their weight. When it ended, their metabolisms had slowed radically and their bodies were not burning enough calories to maintain their thinner sizes.

Researchers knew that just about anyone who deliberately loses weight — even if they start at a normal weight or even underweight — will have a slower metabolism when the diet ends. So they were not surprised to see that “The Biggest Loser” contestants had slow metabolisms when the show ended.

What shocked the researchers was what happened next: As the years went by and the numbers on the scale climbed, the contestants’ metabolisms did not recover. They became even slower, and the pounds kept piling on. It was as if their bodies were intensifying their effort to pull the contestants back to their original weight.

Mr. Cahill was one of the worst off. As he regained more than 100 pounds, his metabolism slowed so much that, just to maintain his current weight of 295 pounds, he now has to eat 800 calories a day less than a typical man his size. Anything more turns to fat.

‘A Basic Biological Reality’

The struggles the contestants went through help explain why it has been so hard to make headway against the nation’s obesity problem, which afflictsmore than a third of American adults. Despite spending billions of dollars on weight-loss drugs and dieting programs, even the most motivated are working against their own biology.

Continue reading the main story

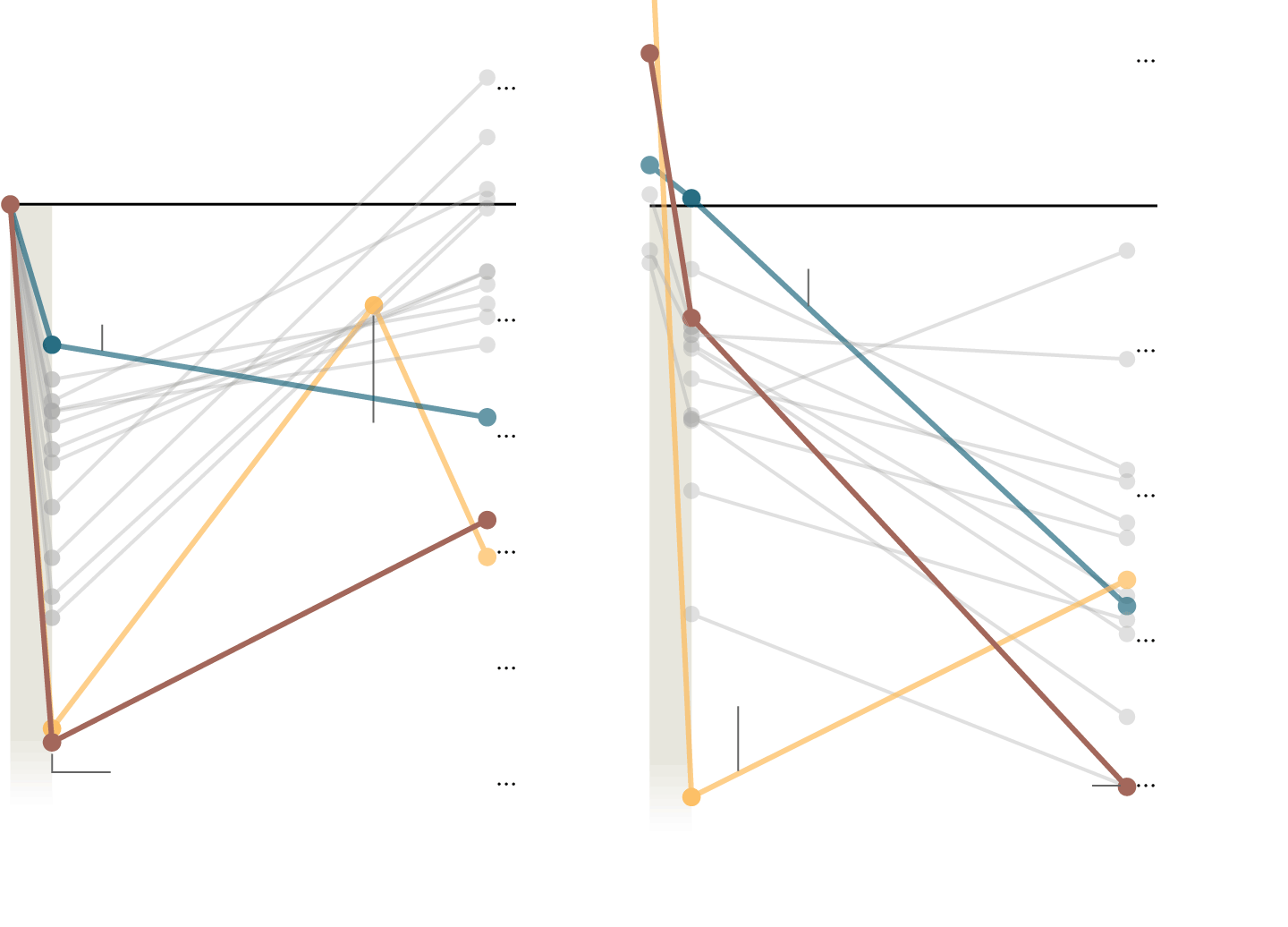

Biggest Losers Fight a Slower Metabolism

A study of contestants from “The Biggest Loser” found their metabolisms slowed during and after the competition, making it difficult to maintain weight loss.

REGAINING LOST WEIGHT

13 of the 14 contestants studied regained weight in the six years after the competition. Four contestants are heavier now than before the competition.

A SLOWING METABOLISM

Nearly all the contestants have slower metabolisms today than they did six years ago, and burn fewer calories than expected when at rest.

Body burns

200 more

cal. a day

GAINED

50 lbs.

0

0

Erinn Egbert is the only contestant who weighs less today than six years ago.

Erinn Egbert

50

200

100

Rudy Pauls regained 80 percent of his lost weight, then had surgery to reduce the size of his stomach.

400

150

600

200

Rudy Pauls

Danny Cahill lost 239 pounds and won the competition, but has regained over 100 pounds.

Danny Cahill now burns 800 fewer calories a day than expected.

Body burns

800 fewer

cal. a day

LOST

250 lbs.

µ

µ

Six years

later

µ

µ

Six years

later

“The Biggest Loser”

Season 8 (2009)

“The Biggest Loser”

Season 8 (2009)

Sources: Obesity; individual contestants

By The New York Times

Their experience shows that the body will fight back for years. And that, said Dr. Michael Schwartz, an obesity and diabetes researcher who is a professor of medicine at the University of Washington, is “new and important.”

“The key point is that you can be on TV, you can lose enormous amounts of weight, you can go on for six years, but you can’t get away from a basic biological reality,” said Dr. Schwartz, who was not involved in the study. “As long as you are below your initial weight, your body is going to try to get you back.”

The show’s doctor, Robert Huizenga, says he expected the contestants’ metabolic rates to fall just after the show, but was hoping for a smaller drop. He questioned, though, whether the measurements six years later were accurate. But maintaining weight loss is difficult, he said, which is why he tells contestants that they should exercise at least nine hours a week and monitor their diets to keep the weight off.

“Unfortunately, many contestants are unable to find or afford adequate ongoing support with exercise doctors, psychologists, sleep specialists, and trainers — and that’s something we all need to work hard to change,” he said in an email.

The study’s findings, to be published on Monday in the journal Obesity, are part of a scientific push to answer some of the most fundamental questions about obesity. Researchers are figuring out why being fat makes so many people develop diabetes and other medical conditions, and they are searching for new ways to block the poison in fat. They are starting to unravel the reasons bariatric surgery allows most people to lose significant amounts of weight when dieting so often fails. And they are looking afresh at medical care for obese people.

Photo

Dina Mercado at home with one of her sons, Jericho, in Commerce, Calif. CreditEmily Berl for The New York Times

Photo

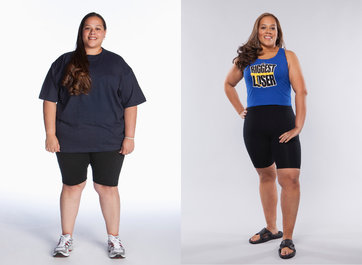

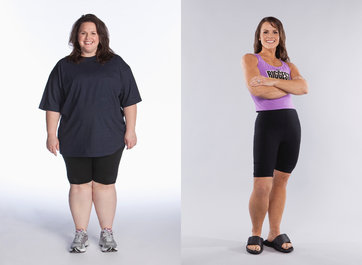

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal via Getty

“It’s hard. The cravings are there.”

Dina Mercado

35, maintenance worker for Commerce, Calif.

WEIGHT Before show, 248 pounds; at finale, 173.5 pounds; now, 205.9 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 437.9 fewer calories per day than would be expected for a woman her size.

There is always a weight a person’s body maintains without any effort. And while it is not known why that weight can change over the years — it may be an effect of aging — at any point, there is a weight that is easy to maintain, and that is the weight the body fights to defend. Finding a way to thwart these mechanisms is the goal scientists are striving for. First, though, they are trying to understand them in greater detail.

Dr. David Ludwig, the director of the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, who was not involved in the research, said the findings showed the need for new approaches to weight control. He cautioned that the study was limited by its small size and the lack of a control group of obese people who did not lose weight. But, he added, the findings made sense.

“This is a subset of the most successful” dieters, he said. “If they don’t show a return to normal in metabolism, what hope is there for the rest of us?”

Still, he added, “that shouldn’t be interpreted to mean we are doomed to battle our biology or remain fat. It means we need to explore other approaches.”

Slimmer and Hungrier

Some scientists say weight maintenance has to be treated as an issue separate from weight loss. Only when that challenge is solved, they say, can progress truly be made against obesity.

“There is a lot of basic research we still need to do,” said Dr. Margaret Jackson, who is directing a project at Pfizer. Her group is testing a drug that, in animals at least, acts like leptin, a hormone that controls hunger. With weight loss, leptin levels fall and people become hungry. The idea is to trick the brains of people who have lost weight so they do not become ravenous for lack of leptin.

While many of the contestants kept enough weight off to improve their health and became more physically active, the low weights they strived to keep eluded all but one of them: Erinn Egbert, a full-time caregiver for her mother in Versailles, Ky. And she struggles mightily to keep the pounds off because her metabolism burns 552 fewer calories a day than would be expected for someone her size.

HEALTH By DEBORAH ACOSTA, ANDREW GLAZER and KAYLE HOPE 3:00

Why It’s Hard to Keep the Pounds Off

Video

Why It’s Hard to Keep the Pounds Off

Rebecca Wright and her husband, Daniel Wright, have gained back a lot of the weight they lost six years ago on Season 8 of "The Biggest Loser." A study of the contestants helps explain why.

By DEBORAH ACOSTA, ANDREW GLAZER and KAYLE HOPE on Publish DateMay 2, 2016. Watch in Times Video »

After ‘The Biggest Loser,’ Their Bodies Fought to Regain Weight

Contestants lost hundreds of pounds during Season 8, but

gained them back. A study of their struggles helps explain

why so many people fail to keep off the weight they lose.

By GINA KOLATAMAY 2, 2016

Danny Cahill stood, slightly dazed, in a blizzard of confetti as the audience screamed and his family ran on stage. He had won Season 8 of NBC’s reality television show “The Biggest Loser,” shedding more weight than anyone ever had on the program — an astonishing 239 pounds in seven months.

When he got on the scale for all to see that evening, Dec. 8, 2009, he weighed just 191 pounds, down from 430. Dressed in a T-shirt and knee-length shorts, he was lean, athletic and as handsome as a model.

“I’ve got my life back,” he declared. “I mean, I feel like a million bucks.”

Mr. Cahill left the show’s stage in Hollywood and flew directly to New York to start a triumphal tour of the talk shows, chatting with Jay Leno, Regis Philbin and Joy Behar. As he heard from fans all over the world, his elation knew no bounds.

But in the years since, more than 100 pounds have crept back onto his 5-foot-11 frame despite his best efforts. In fact, most of that season’s 16 contestants have regained much if not all the weight they lost so arduously. Some are even heavier now.

Yet their experiences, while a bitter personal disappointment, have been a gift to science. A study of Season 8’s contestants has yielded surprising new discoveries about the physiology of obesity that help explain why so many people struggle unsuccessfully to keep off the weight they lose.

Kevin Hall, a scientist at a federal research center who admits to a weakness for reality TV, had the idea to follow the “Biggest Loser” contestants for six years after that victorious night. The project was the first to measure what happened to people over as long as six years after they had lost large amounts of weight with intensive dieting and exercise.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Photo

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal, via Getty

“I won’t be victim to this. It’s the hand I’ve been dealt.”

Danny Cahill

46, speaker, author, land surveyor and musician, Broken Arrow, Okla.

WEIGHT Before show, 430 pounds; at finale, 191 pounds; now, 295 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 800 fewer calories a day than would be expected for a man his size.

The results, the researchers said, were stunning. They showed just how hard the body fights back against weight loss.

“It is frightening and amazing,” said Dr. Hall, an expert on metabolism at the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, which is part of the National Institutes of Health. “I am just blown away.”

It has to do with resting metabolism, which determines how many calories a person burns when at rest. When the show began, the contestants, though hugely overweight, had normal metabolisms for their size, meaning they were burning a normal number of calories for people of their weight. When it ended, their metabolisms had slowed radically and their bodies were not burning enough calories to maintain their thinner sizes.

Researchers knew that just about anyone who deliberately loses weight — even if they start at a normal weight or even underweight — will have a slower metabolism when the diet ends. So they were not surprised to see that “The Biggest Loser” contestants had slow metabolisms when the show ended.

What shocked the researchers was what happened next: As the years went by and the numbers on the scale climbed, the contestants’ metabolisms did not recover. They became even slower, and the pounds kept piling on. It was as if their bodies were intensifying their effort to pull the contestants back to their original weight.

Mr. Cahill was one of the worst off. As he regained more than 100 pounds, his metabolism slowed so much that, just to maintain his current weight of 295 pounds, he now has to eat 800 calories a day less than a typical man his size. Anything more turns to fat.

‘A Basic Biological Reality’

The struggles the contestants went through help explain why it has been so hard to make headway against the nation’s obesity problem, which afflictsmore than a third of American adults. Despite spending billions of dollars on weight-loss drugs and dieting programs, even the most motivated are working against their own biology.

Continue reading the main story

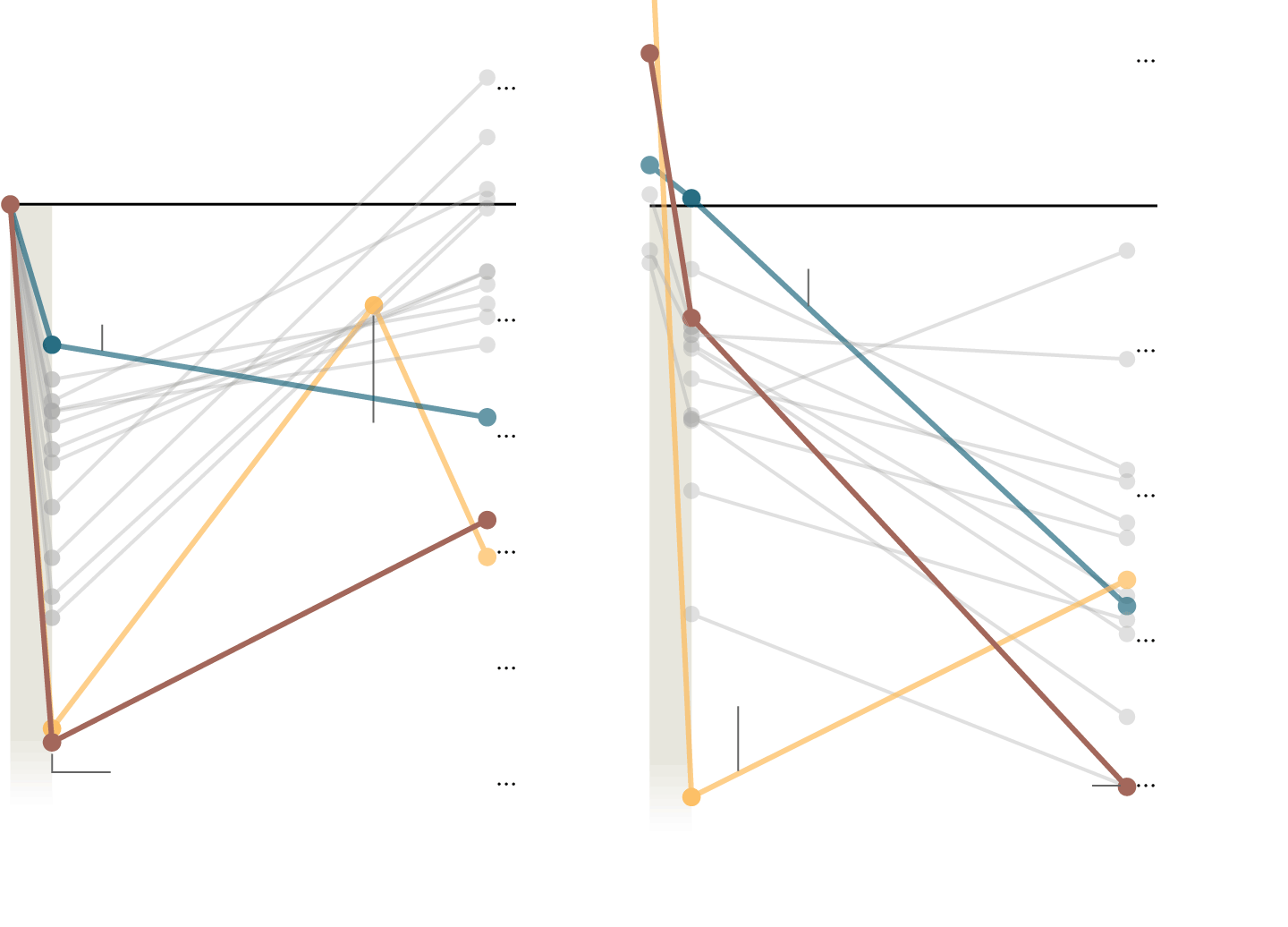

Biggest Losers Fight a Slower Metabolism

A study of contestants from “The Biggest Loser” found their metabolisms slowed during and after the competition, making it difficult to maintain weight loss.

REGAINING LOST WEIGHT

13 of the 14 contestants studied regained weight in the six years after the competition. Four contestants are heavier now than before the competition.

A SLOWING METABOLISM

Nearly all the contestants have slower metabolisms today than they did six years ago, and burn fewer calories than expected when at rest.

Body burns

200 more

cal. a day

GAINED

50 lbs.

0

0

Erinn Egbert is the only contestant who weighs less today than six years ago.

Erinn Egbert

50

200

100

Rudy Pauls regained 80 percent of his lost weight, then had surgery to reduce the size of his stomach.

400

150

600

200

Rudy Pauls

Danny Cahill lost 239 pounds and won the competition, but has regained over 100 pounds.

Danny Cahill now burns 800 fewer calories a day than expected.

Body burns

800 fewer

cal. a day

LOST

250 lbs.

µ

µ

Six years

later

µ

µ

Six years

later

“The Biggest Loser”

Season 8 (2009)

“The Biggest Loser”

Season 8 (2009)

Sources: Obesity; individual contestants

By The New York Times

Their experience shows that the body will fight back for years. And that, said Dr. Michael Schwartz, an obesity and diabetes researcher who is a professor of medicine at the University of Washington, is “new and important.”

“The key point is that you can be on TV, you can lose enormous amounts of weight, you can go on for six years, but you can’t get away from a basic biological reality,” said Dr. Schwartz, who was not involved in the study. “As long as you are below your initial weight, your body is going to try to get you back.”

The show’s doctor, Robert Huizenga, says he expected the contestants’ metabolic rates to fall just after the show, but was hoping for a smaller drop. He questioned, though, whether the measurements six years later were accurate. But maintaining weight loss is difficult, he said, which is why he tells contestants that they should exercise at least nine hours a week and monitor their diets to keep the weight off.

“Unfortunately, many contestants are unable to find or afford adequate ongoing support with exercise doctors, psychologists, sleep specialists, and trainers — and that’s something we all need to work hard to change,” he said in an email.

The study’s findings, to be published on Monday in the journal Obesity, are part of a scientific push to answer some of the most fundamental questions about obesity. Researchers are figuring out why being fat makes so many people develop diabetes and other medical conditions, and they are searching for new ways to block the poison in fat. They are starting to unravel the reasons bariatric surgery allows most people to lose significant amounts of weight when dieting so often fails. And they are looking afresh at medical care for obese people.

Photo

Dina Mercado at home with one of her sons, Jericho, in Commerce, Calif. CreditEmily Berl for The New York Times

Photo

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal via Getty

“It’s hard. The cravings are there.”

Dina Mercado

35, maintenance worker for Commerce, Calif.

WEIGHT Before show, 248 pounds; at finale, 173.5 pounds; now, 205.9 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 437.9 fewer calories per day than would be expected for a woman her size.

There is always a weight a person’s body maintains without any effort. And while it is not known why that weight can change over the years — it may be an effect of aging — at any point, there is a weight that is easy to maintain, and that is the weight the body fights to defend. Finding a way to thwart these mechanisms is the goal scientists are striving for. First, though, they are trying to understand them in greater detail.

Dr. David Ludwig, the director of the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center at Boston Children’s Hospital, who was not involved in the research, said the findings showed the need for new approaches to weight control. He cautioned that the study was limited by its small size and the lack of a control group of obese people who did not lose weight. But, he added, the findings made sense.

“This is a subset of the most successful” dieters, he said. “If they don’t show a return to normal in metabolism, what hope is there for the rest of us?”

Still, he added, “that shouldn’t be interpreted to mean we are doomed to battle our biology or remain fat. It means we need to explore other approaches.”

Slimmer and Hungrier

Some scientists say weight maintenance has to be treated as an issue separate from weight loss. Only when that challenge is solved, they say, can progress truly be made against obesity.

“There is a lot of basic research we still need to do,” said Dr. Margaret Jackson, who is directing a project at Pfizer. Her group is testing a drug that, in animals at least, acts like leptin, a hormone that controls hunger. With weight loss, leptin levels fall and people become hungry. The idea is to trick the brains of people who have lost weight so they do not become ravenous for lack of leptin.

While many of the contestants kept enough weight off to improve their health and became more physically active, the low weights they strived to keep eluded all but one of them: Erinn Egbert, a full-time caregiver for her mother in Versailles, Ky. And she struggles mightily to keep the pounds off because her metabolism burns 552 fewer calories a day than would be expected for someone her size.

HEALTH By DEBORAH ACOSTA, ANDREW GLAZER and KAYLE HOPE 3:00

Why It’s Hard to Keep the Pounds Off

Video

Why It’s Hard to Keep the Pounds Off

Rebecca Wright and her husband, Daniel Wright, have gained back a lot of the weight they lost six years ago on Season 8 of "The Biggest Loser." A study of the contestants helps explain why.

By DEBORAH ACOSTA, ANDREW GLAZER and KAYLE HOPE on Publish DateMay 2, 2016. Watch in Times Video »

- studyfunded by Australia’s National Health and Medical Research Council, Dr. Joseph Proietto of the University of Melbourne and his colleagues recruited 50 overweight people who agreed to consume just 550 calories a day for eight or nine weeks. They lost an average of nearly 30 pounds, but over the next year, the pounds started coming back.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Sean Algaier taking communion at Providence Road Church of Christ in Charlotte, N.C., where he is a pastor.CreditGeorge Etheredge for The New York Times

Photo

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal via Getty

“It’s not as dramatic as being told you have a disease, but it’s along those lines.”

Sean Algaier

36, worship pastor, Charlotte, N.C.

WEIGHT Before show, 444 pounds; at finale, 289 pounds; now, 450 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 458 fewer calories a day than would be expected for a man his size.

Dr. Proietto and his colleagues looked at leptin and four other hormones that satiate people. Levels of most of them fell in their study subjects. They also looked at a hormone that makes people want to eat. Its level rose.

“What was surprising was what a coordinated effect it is,” Dr. Proietto said. “The body puts multiple mechanisms in place to get you back to your weight. The only way to maintain weight loss is to be hungry all the time. We desperately need agents that will suppress hunger and that are safe with long-term use.”

370, 400, 460, 485

Mr. Cahill, 46, said his weight problem began when he was in the third grade. He got fat, then fatter. He would starve himself, and then eat a whole can of cake frosting with a spoon. Afterward, he would cower in the pantry off the kitchen, feeling overwhelmed with shame.

Over the years, his insatiable urge to eat kept overcoming him, and his weight climbed: 370 pounds, 400, 460, 485.

“I used to look at myself and think, ‘I am horrible, I am a monster, subhuman,’” he said. He began sleeping in a recliner because he was too heavy to sleep lying down. Walking hurt; stairs were agony. Buying clothes with a 68 waist was humiliating.

“I remember sitting in a dressing room one day, and nothing would fit. I looked at the traffic outside on the street and thought, ‘I should just run out in front of a car.’”

He eventually seized on “The Biggest Loser” as his best chance to lose enough weight to live a normal life. He tried three times and was finally selected.

Sign up to receive an email

We will inform you when the next Times report from the "Science of Fat" series is published.

Sign Me Up

Before the show began, the contestants underwent medical tests to be sure they could endure the rigorous schedule that lay ahead. And rigorous it was. Sequestered on the “Biggest Loser” ranch with the other contestants, Mr. Cahill exercised seven hours a day, burning 8,000 to 9,000 calories according to a calorie tracker the show gave him. He took electrolyte tablets to help replace the salts he lost through sweating, consuming many fewer calories than before.

Eventually, he and the others were sent home for four months to try to keep losing weight on their own.

Mr. Cahill set a goal of a 3,500-caloric deficit per day. The idea was to lose a pound a day. He quit his job as a land surveyor to do it.

His routine went like this: Wake up at 5 a.m. and run on a treadmill for 45 minutes. Have breakfast — typically one egg and two egg whites, half a grapefruit and a piece of sprouted grain toast. Run on the treadmill for another 45 minutes. Rest for 40 minutes; bike ride nine miles to a gym. Work out for two and a half hours. Shower, ride home, eat lunch — typically a grilled skinless chicken breast, a cup of broccoli and 10 spears of asparagus. Rest for an hour. Drive to the gym for another round of exercise.

If he had not burned enough calories to hit his goal, he went back to the gym after dinner to work out some more. At times, he found himself running around his neighborhood in the dark until his calorie-burn indicator reset to zero at midnight.

On the day of the weigh-in on the show’s finale, Mr. Cahill and the others dressed carefully to hide the rolls of loose skin that remained, to their surprise and horror, after they had lost weight. They wore compression undergarments to hold it in.

Mr. Cahill knew he could not maintain his finale weight of 191 pounds. He was so mentally and physically exhausted he barely moved for two weeks after his publicity tour ended. But he had started a new career giving motivational speeches as the biggest loser ever, and for the next four years, he managed to keep his weight below 255 pounds by exercising two to three hours a day. But two years ago, he went back to his job as a surveyor, and the pounds started coming back.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Armanda Arlauskas walking her dog, Jax, in her neighborhood in Raleigh, N.C. CreditGeorge Etheredge for The New York Times

Photo

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal via Getty

“I could tell something wasn’t right with my body. I just knew it was an issue with my metabolism.”

Amanda Arlauskas

26, wellness coach and social media consultant, Raleigh, N.C.

WEIGHT Before show, 250 pounds; at finale, 163 pounds; now, 176 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 591.1 fewer calories per day than would be expected for a woman her size.

Soon the scale hit 265. Mr. Cahill started weighing and measuring his food again and stepped up his exercise. He got back down to 235 to 240 pounds. But his weight edged up again, to 275, then 295.

His slow metabolism is part of the problem, and so are his food cravings. He opens a bag of chips, thinking he will have just a few. “I’d eat five bites. Then I’d black out and eat the whole bag of chips and say, ‘What did I do?’”

Brain Sets the Calories

Dr. Lee Kaplan, an obesity researcher at Harvard, says the brain sets the number of calories we consume, and it can be easy for people to miss that how much they eat matters less than the fact that their bodies want to hold on to more of those calories.

Dr. Michael Rosenbaum, an obesity researcher at Columbia University who has collaborated with Dr. Hall in previous studies, said the body’s systems for regulating how many calories are consumed and how many are burned are tightly coupled when people are not strenuously trying to lose weight or to maintain a significant weight loss. Still, pounds can insidiously creep on.

“We eat about 900,000 to a million calories a year, and burn them all except those annoying 3,000 to 5,000 calories that result in an average annual weight gain of about one to two pounds,” he said. “These very small differences between intake and output average out to only about 10 to 20 calories per day — less than one Starburst candy — but the cumulative consequences over time can be devastating.”

“It is not clear whether this small imbalance and the resultant weight gain that most of us experience as we age are the consequences of changes in lifestyle, the environment or just the biology of aging,” Dr. Rosenbaum added.

The effects of small imbalances between calories eaten and calories burned are more pronounced when people deliberately lose weight, Dr. Hall said. Yes, there are signals to regain weight, but he wondered how many extra calories people were driven to eat. He found a way to figure that out.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Rudy Pauls and his wife, Beth, disinfecting a newborn lamb on their farm in Belchertown, Mass.CreditNathaniel Brooks for The New York Times

Photo

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal via Getty

“‘The Biggest Loser’ did change my life, but not in a way that most would think. It opened my eyes to the fact that obesity is not simply a food addiction. It is a disability of a malfunctioning metabolic system.”

Rudy Pauls

37, electrical engineer, Belchertown, Mass.

WEIGHT Before show, 442 pounds; at finale, 234 pounds; in 2014, 390 pounds; now, after bariatric surgery, 265 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 516 fewer calories a day than would be expected for a man his size.

He analyzed data from a clinical trial in which people took a diabetes drug,canagliflozin, that makes them spill 360 calories a day into their urine, or took a placebo. The drug has no known effect on the brain, and the person does not realize those calories are being spilled. Those taking the drug gradually lost weight. But for every five pounds they lost, they were, without realizing it, eating an additional 200 calories a day.

Those extra calories, Dr. Hall said, were a bigger driver of weight regained than the slowing of the metabolism. And, he added, if people fought the urge to eat those calories, they would be hungry. “Unless they continue to fight it constantly, they will regain the weight,” he said.

All this does not mean that modest weight loss is hopeless, experts say. Individuals respond differently to diet manipulations — low-carbohydrate or low-calorie diets, for example — and to exercise and weight-loss drugs, among other interventions.

But Dr. Ludwig said that simply cutting calories was not the answer. “There are no doubt exceptional individuals who can ignore primal biological signals and maintain weight loss for the long term by restricting calories,” he said, but he added that “for most people, the combination of incessant hunger and slowing metabolism is a recipe for weight regain — explaining why so few individuals can maintain weight loss for more than a few months.”

Dr. Rosenbaum agreed. “The difficulty in keeping weight off reflects biology, not a pathological lack of willpower affecting two-thirds of the U.S.A.,” he said.

1700COMMENTS

Mr. Cahill knows that now. And with his report from Dr. Hall’s group showing just how much his metabolism had slowed, he stopped blaming himself for his weight gain.

“That shame that was on my shoulders went off,” he said.

Continue reading the main story

Continue reading the main story

Photo

Tracey Yukich walks regularly at Lake Johnson Park in Raleigh, N.C. CreditGeorge Etheredge for The New York Times

Photo

BEFORE and AT FINALECreditLeft: Chris Haston/NBC Universal via Getty; Right: Trae Patton/NBC Universal via Getty

“I eat very clean and stay away from sugar, and I take supplements. I want to know what do we do now, because I am a doer.”

Tracey Yukich

44, exercise physiologist, Raleigh, N.C.

WEIGHT Before show, 250 pounds; at finale, 132 pounds; now, 178 pounds

METABOLIC RATE Now burns 211.7 fewer calories per day than would be expected for a woman her size.

Larra

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Dec 31, 2013

- Messages

- 3,558

I recall, before my DS (meaning over 10 years ago) there was an article from Marceau about the metabolic effects of being MO and how losing weight actually made them worse. As much as I detest that TV show for exploiting fat people, I'm glad it's bringing this knowledge about how and why it's so difficult to lose and keep off weight to the general public, you know, all those people who think we just need more will power, or to exercise by pushing ourselves away from the table.

Any way we could have this article as a sticky?? Not for the general public, but for all the people who are still kicking themselves for needing bariatric surgery, or for not succeeding with a purely restrictive procedure.

Any way we could have this article as a sticky?? Not for the general public, but for all the people who are still kicking themselves for needing bariatric surgery, or for not succeeding with a purely restrictive procedure.

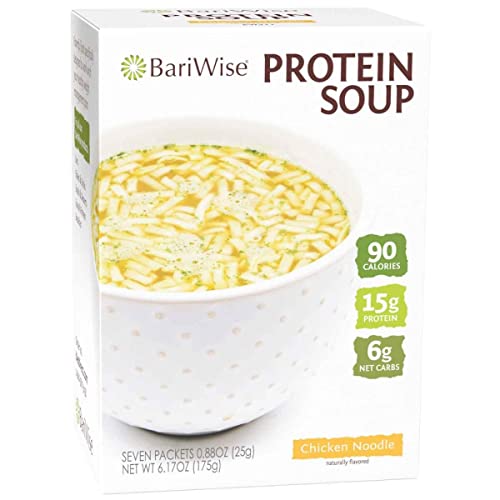

$9.29

$14.95

Gastric Bypass Recipes: 80+ Simple Recipes for the First Stage After Gastric Bypass Surgery (Bariatric Cookbook)

Amazon.com

$19.87 ($0.17 / Count)

$29.97 ($0.25 / Count)

PAWFECTCHEW Pawfect Mobility - Glucosamine Treats for Dogs - Hip & Joint Health Supplement Chews w/Omega-3, Chondroitin, MSM - Made in USA - Joint Pain Relief - Hip & Joint Care - 120ct

PawfectSupplies

$9.49

$15.99

Fresh Start Bariatric Cookbook: Healthy Recipes to Enjoy Favorite Foods After Weight-Loss Surgery

Amazon.com

$10.17

$18.99

The Complete Bariatric Cookbook and Meal Plan: Recipes and Guidance for Life Before and After Surgery

Amazon.com

$16.79 ($1.48 / Ounce)

$19.99 ($1.76 / Ounce)

Quest Nutrition Mini Cookies & Cream Protein Bars, 8g Protein, 1g Sugar, 2g Net Carbs, Gluten Free, 14 Count

Amazon.com

$41.00

Walttools Tru Tex CORAL Texture Roller Sleeve for Concrete Flatwork and Vertical Concrete - Quick, Easy, Realistic Patterns, User-Friendly (Coral Stone)

Decorative Concrete Supply Source

$10.00 ($10.00 / Count)

First Days Maternity - Maxi Peri Bottle for Maximum Postpartum Soothing! Large 650ml Capacity Allows for an Effective Soothe. Pink Colour

First Days Maternity

$16.99 ($0.39 / Ounce)

BariWise Protein Soup Mix, Chicken Noodle, 15g Protein, Low Carb (7ct).

DIET DIRECT

$44.75 ($1.23 / Ounce)

$54.75 ($1.50 / Ounce)

LIVING HEALTHY NUTRITION BariSuccess Vanilla Whey Isolate Protein Powder - 30g Protein, 30 Servings/Container - Free of Fat, Sugar, Gluten, Soy & Lactose - Low Carb Bariatric Meal Replacement Protein

My Bariatric Kitchen

$11.36

$14.95

Gastric Bypass Diet: Step By Step Guide to Gastric Bypass Surgery (Bariatric Cookbook)

Amazon.com

$17.29 ($8.64 / Count)

$18.49 ($9.24 / Count)

Bariatric Portion Control Plates for Weight Loss - Perfect for Bariatric Surgery Patients, Portion Control Containers for Easy Weight Management and Healthy Eating Habits - 2 Pack

Universal Body Labs

$8.99

$15.99

The Gastric Sleeve Bariatric Cookbook: Easy Meal Plans and Recipes to Eat Well & Keep the Weight Off

Amazon.com

newanatomy

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 5, 2014

- Messages

- 2,983

I recall, before my DS (meaning over 10 years ago) there was an article from Marceau about the metabolic effects of being MO and how losing weight actually made them worse. As much as I detest that TV show for exploiting fat people, I'm glad it's bringing this knowledge about how and why it's so difficult to lose and keep off weight to the general public, you know, all those people who think we just need more will power, or to exercise by pushing ourselves away from the table.

Any way we could have this article as a sticky?? Not for the general public, but for all the people who are still kicking themselves for needing bariatric surgery, or for not succeeding with a purely restrictive procedure.

It's now sticky.

aaa

Well-Known Member

Distressing but not unexpected.

Jennie1980

Active Member

- Joined

- Apr 21, 2016

- Messages

- 35

I read this yesterday and found it heartbreaking. I really feel bad for people on the yo-yo. I am a firm believer in the body's preference for a certain weight in both directions. I'm a lightweight. 2 more monthly visits to my primary care for the monthly supervised dieting. My body likes to be 187lbs. No less and also no more. At my height of 5'3 that's not a BMI if 35. The surgeon said don't lose a lb when I saw him and I was up a little then. Since I quit smoking, I'm snacking. I got to a point that I wasn't worried of being rejected by insurance, my BMI was right where it needed to be and all the sudden, I poop. A lot. For no good reason. I've been constipated my entire life. Now I can't stop with the poops. I don't think I'm sick. Feel fine otherwise. (Except muscle pain from statins which I will never take again) My body wants me to weigh 187lbs. No more. No less. I'm pretty tired of fighting it too. With several new diagnosis and just being worn out with being sick, my body needs to let go with its insistence on a certain weight. I'm about to start a round of prednisone so that ought to tip the scales where I need to be. I can gain a bunch quickly but I go right back. And because of pain, I am not exercising. In fact, I'm hardly moving.

Please don't think I'm a jackass for being "not fat enough." Getting The DS is important to me because my health sucks. Sure I want to be slimmer but I'm pretty sick of being sick. I know it could be worse. It has been worse.

Please don't think I'm a jackass for being "not fat enough." Getting The DS is important to me because my health sucks. Sure I want to be slimmer but I'm pretty sick of being sick. I know it could be worse. It has been worse.

Spiky Bugger

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 5, 2014

- Messages

- 6,310

I read this yesterday and found it heartbreaking. I really feel bad for people on the yo-yo. I am a firm believer in the body's preference for a certain weight in both directions. I'm a lightweight. 2 more monthly visits to my primary care for the monthly supervised dieting. My body likes to be 187lbs. No less and also no more. At my height of 5'3 that's not a BMI if 35. The surgeon said don't lose a lb when I saw him and I was up a little then. Since I quit smoking, I'm snacking. I got to a point that I wasn't worried of being rejected by insurance, my BMI was right where it needed to be and all the sudden, I poop. A lot. For no good reason. I've been constipated my entire life. Now I can't stop with the poops. I don't think I'm sick. Feel fine otherwise. (Except muscle pain from statins which I will never take again) My body wants me to weigh 187lbs. No more. No less. I'm pretty tired of fighting it too. With several new diagnosis and just being worn out with being sick, my body needs to let go with its insistence on a certain weight. I'm about to start a round of prednisone so that ought to tip the scales where I need to be. I can gain a bunch quickly but I go right back. And because of pain, I am not exercising. In fact, I'm hardly moving.

Please don't think I'm a jackass for being "not fat enough." Getting The DS is important to me because my health sucks. Sure I want to be slimmer but I'm pretty sick of being sick. I know it could be worse. It has been worse.

I get it.

My sister, 5'2", well over 300#, had the VSG in October of 2011.

When she got down to 182#, and had, in her mind, 50# more to lose, she started TRYING to get to her personal goal. She had plastics, to remove LOTS of excess skin between waist and buttocks. She still has LOTS of excess skin between hips and knees.

But...she now weighs 225#.

So, 4.5 years out, she has "kept" the regain to an average of ten pounds per year. Which means she is doing better than average...but not "well."

Her body is working at going back to where it was.

Pattycake813

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Apr 22, 2016

- Messages

- 227

Not going to lie, this is one of my biggest fears. .. That I will lose 60 lbs and stop, or get to my goal and just slowly creep back up to 300. I know that with the DS it is highly unlikely.. But I'd be lying if I didn't say the thought scares the crap out of me

Spiky Bugger

Well-Known Member

- Joined

- Jan 5, 2014

- Messages

- 6,310

Not going to lie, this is one of my biggest fears. .. That I will lose 60 lbs and stop, or get to my goal and just slowly creep back up to 300. I know that with the DS it is highly unlikely.. But I'd be lying if I didn't say the thought scares the crap out of me

Even with the DS, it can be done. But MOST of the people I know of who lost a ton and regained it were also drinking many of their calories. Often booze. Often non-stop soft drinks. It is harder to do, and easier to correct, with just food.

My weight loss has been up and down. I stopped dead from 293 to 205 at one year out. Stayed there with no difficulty until 3.3 years out, when I started losing again. Encouraged, I started working out too. Ended up losing down to 170, and scheduled major reconstructive surgery. Had the first procedure, had terrible side effects from medication, ended up needing antidepressants and gained back 35 lbs (obviously, MY set point). Sat there for a few years, then over the last year or so, became very sedentary - probably lost a lot of muscle mass, which is NOT good, but also stopped eating as much, so I assume SOME of the loss is fat. I'm now - at closing in on 13 years out - at about 183, and trickling down. I'm hoping I can find my teenaged set point of 148 (which I thought was FAT!) someday. But I'm not even remotely setting that as an actual goal. 170 would be good.

Similar threads

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 387

- Replies

- 117

- Views

- 6K

- Replies

- 6

- Views

- 2K